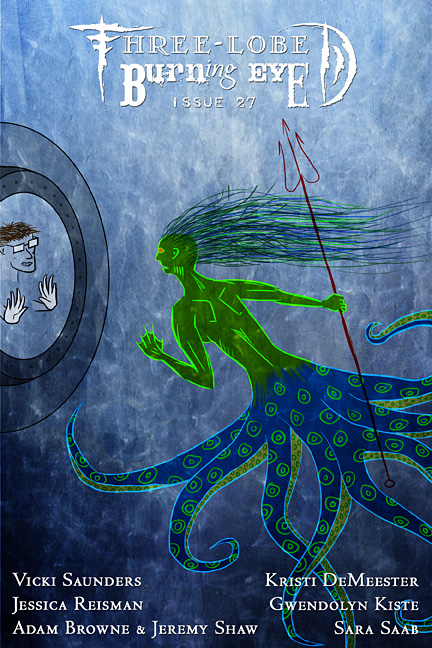

Little Seller of La Quarantaine

by Sara Saab

6456 words

© 2015 Sara Saab

On the day we dropped anchor at that famous port, I distributed nineteen new pairs of socks among the crew of the Tridente. Our progress had been delayed by angry, low clouds, a howling wind, and a discreet argument among the captain’s trusted sailors.

I was privy to nothing, but I heard a lot. I knit by the ship’s stove, where the warmth gathered longest like a ghostly companion. I sewed in a nook adjacent to the captain’s chamber beneath a hanging candle, and I saw all manner of visitors knock at his door. I was all but sure of the nature of his common interests with Diego, the young navigator hired at Malaga to get us all the way around the cape to Ceylon. I also knew the proud captain sought advice from the clever sailor Vasco, who was an ex-criminal with the look of a crooked man, although he had never done wrong by me.

Many of the sailors aboard were not as kind. “Darra!” they screamed from the deck, expecting me to hear them over the roar of waves. “The patch you put in the seat of these slacks has torn right off in two days, you stupid bitch!”

I would go to fetch the slacks, or the shirt missing its buttons, or the boot with the flapping sole. The sailors would remove the offending items, swat me with them across the head, shout, strike me with open hands. They implored the captain to throw me overboard.

I was not a young woman, and had borne two cherubic girls, dead of fever before their third and fifth birthdays. But I was not immune to the perverse appetites of these sailors. They curled their fists in my tailor’s apron and whispered as if dying. They hurt me, cut me viciously with the cruelty of their bodies. What was I to do, on the wide ocean, with no home or family left to me at any port?

For all that I knew of this ship and its men — for all that I knew of their habits and secrets — I did not know what agitation delayed our landing at Beyrouth. It was a very quiet worry, a very deep one, and it was so sour aboard the Tridente that we seemed to attract the heaviest of clouds.

As dark as those days were, the morning we bobbed to our mooring post in that famed port of the Levant, that gateway to the East, the sun was smiling widely on the bountiful land of the Syrians. Distant snow-capped mountains shone like jellyfish in shallow water.

It was not long before the captain sent a boat ashore to herald our arrival. The crew prepared their belongings and what cargo was destined for trade here. I collected the extent of my possessions: one change of clothing, my sewing needles, my thread, and my enameled box of buttons.

The boatman soon rowed back with news that dampened the crew’s mood even further. We were to report at La Quarantaine, the lazaretto of Beyrouth, before being allowed to sail for Ceylon.

We would be held there for no less than a fortnight by order of Ibrahim Pasha, the Ottoman ruler of Beyrouth. The boatman had been told of the Pasha’s strict policy that no scourge would spread through that trading route. Vasco quipped to the captain that siphoning gold off merchant seamen was easier, too, if you forcibly held them at your port.

I often imagined that I had a wall inside of me, and I put my back to it to steady me when my times were hard. This way I withstood hardship, and my wall only ever failed me when my girls caught the wasting fever and died within a month of each other. At this gloomy news, I pressed myself against my wall, and spoke frankly to myself — Darra, for you all destinations are interchangeable. Two weeks in quarantine mean nothing more nor less than two weeks longer at sea. You have nowhere else worth being.

I held onto the small relief of soon walking on solid earth, and the reprieve from the creaking dark cubby holes which were my warrens aboard the ship.

• • •

The old cook and I, being the only women, were appointed our own rooms near the entrance of the lazaretto, apart from the men. When I went to relieve myself, I met a sailor named Morizio on his way out of the shared outhouse, little more than a hole in the ground.

Morizio seemed tired, harried. We were all so, having travelled long weeks on an upset sea. But he looked more than tired. He seemed ill. Water or sweat drenched the collar of his tunic, and his eyes were wide and desperate, like those of a drowning man. He half stumbled past me, and I smelled vomit on his breath. Air was heaving out of his lungs as if from a bellows.

Morizio had only mistreated me once to gain favor and laughs from the established crew, and so I did not think him a rotten soul. Still, facing him in that state put a shiver in my spine, and I connected the incident back to the secret commotion on board our ship.

I began to worry that perhaps Ibrahim Pasha’s men were right to detain us at La Quarantaine after all. If a terrible pestilence plagued the Tridente’s crew, there was no one I could exchange thoughts with, no one I held in high enough confidence to speak to. Even if I could, what would I say?

• • •

It was as I stood at my window that I heard confused, gruff noises from the cook’s room, followed a few instants later by a hollow patter at my door.

I did not hesitate to unlatch the door and pull it open. There was nothing intimate to me that the world had not already ravaged, and the shelter of locked doors was not a protection I was used to.

In the doorway stood a child, about six years old. It had a bronzed complexion, splotchy with the spread of sweat and dust residue across its face. Its head was chaotically crowned by a rumpled nest of hair, dark as soot. Cunning eyes with big whites studied me without passing discernable judgment.

The urchin was of unclear gender. It wore sequined slippers with almost no sequins left upon them, billowing slacks, and a gilet in a maroon shade, torn under the left armpit. Its eyes were kohled, its lips reddened.

“What do you have there?” I asked in Spanish. I did not expect the child to know languages, but made my voice a friendly sing-song to hold the creature on the doorstep.

The child carried an impressive array of items in those small arms. Its right arm and shoulder supported a chain of small ceramic cups painted with a floral motif. At least twenty of these cups slotted inside one another, snaking up to nestle in the nook of a small jaw. The left arm balanced what looked like a repurposed cigar box with two compartments, one heaped with drops of chewing resin, and the other with dragees of white sugar. Not content with this burden, the left elbow also hooked a leather and canvas bladder which sagged with a liquid content.

“Come in, little seller,” I said, and swung the door wider.

The child shrugged the snake of cups into a safer arrangement, retreated into the shadow of the corridor, and returned nudging a marvelous rattling tricycle into my room with one foot.

A wooden horse was hitched to an iron wheel in the front, and behind the seat, a copper pot with a long spout sat in a special net. As the youngster inched the tricycle forward, the copper pot sloshed, and the room was perfumed with the vapors of a pungent oriental coffee.

“I don’t have any money,” I continued in Spanish, and my chest ached with the disappointment in the little one’s eyes. Young as it was, the child understood blows to its livelihood dealt in any language.

Then I had a more painful memory, of playing with my younger girl, Aleja, a game of trade. She would call on me to sell me pretty stones, hibernating snails, wilted flowers, and I would pay her with…

I lifted my pallet and fished out my enameled box of buttons.

“Will you take a few buttons?” I asked, gesturing at the pot of coffee, and a sugar dragee, then selecting two buttons. I held them like coins.

The child’s brow knitted sternly at the sight of them. It was enough to prompt a disburdening of the collection of carried wares. These the little one laid one by one on the carpeted floor, except for the chain of cups, which was first divided into five shorter stacks that would balance when set down.

I felt a shake in my heart as this industrious creature drew near. A small hand cupped mine to examine the handsome buttons, one purple with a gilt border, the other ivory colored and patterned. I caught the child’s scent--not a washed smell, but not a repulsive smell either. Earthy and musky. The closeness reminded me painfully of my daughters, and I realized this was the first child to approach me since their deaths.

The buttons were found to be an acceptable barter.

After pocketing them, the seller unhitched the copper pot, poured a long drizzle of steaming coffee into one of the ceramic cups, and presented it to me with the box of sweets. I chose a block of sugar and put it under my tongue to dissolve. I savored the coffee over many small sips. The cardamom and cloves played a tune on my tongue.

The child watched me, long lashes beating when it blinked.

“Nur!” it announced suddenly, both palms to its chest.

“Darra,” I replied, pointing at my smiling face. I did not know how to ask, so I decided the lazaretto’s peddler could be a girl, like my two angels, but so unlike either of them.

• • •

The knock on the door came early. The second pair of socks still needed ribbing, and I had not readied myself for the day. I hurried to hide my unfinished knitting before opening the door.

A large frame filled my doorway. It was Carles, a Tridente crewman. He had been especially cruel since the first time he’d seen me. The day I joined the crew, the Tridente had been moored in choppy waters and driving rain, but Carles thought it amusing to let down just a thin, wobbling plank of wood for me to clamber up to reach the deck.

“Darra,” he said. “It’s been strange to do without the services of our talented tailor since we docked.” He let himself in. “I’d even say it has been somewhat lonely without you.”

Instinctively, I backed into my room, almost tripping on the edge of a Turkish rug where it overlaid another.

“I had planned to report to the captain today for any work to be done, sir,” I replied, though I could see on the sailor’s weatherworn face a message of mischief and cruelty.

His visit was not on the captain’s behalf.

“Well, you could help me with some work to be done.” Carles paused when he saw me glance at his hands. I was still hoping to find a sewing job there. He laughed merrily and approached me, grabbed the apron I had just put on, and ripped it away with a swipe.

“You need something to fix so bad, you old bitch? Fix that, if you must. But later.”

He cupped my jaw in a searing grip. I tottered forward to protect my craning neck. Carles studied my face as if examining a donkey foal before agreeing to a purchase.

“Damn, you ugly hag! You never looked this bad below deck in one of your little rabbitholes. What shit luck leaves a man a choice between the hairless toothless turnip next door and a hag with skin drooping from her body like a half-skinned chicken?”

As shameful as it sounds, I willed myself to seem yet uglier, less female. I wished to myself I could have stoppered my sex with molten lead. But I knew that would hardly slow a man like Carles down. That I was a woman was an excuse. What he thirsted for was my humiliation, whatever shape that took.

To hold my composure, I willed myself to search Carles’ face for any signs of a mysterious illness. Sweat tracked down his temples, but Beyrouth was hot; a rich sun serenaded the city every morning and left in its wake a clotted haze of day. Carles’ lips were cracked, his eyes bloodshot beneath the slugs of his eyebrows.

He might have been in the early or last rounds of an illness, or he might have slept fitfully his first night on solid ground. It was impossible to tell.

“I cannot breathe,” I mustered through a compressed throat. Carles softened his clutch on my neck then started unbuttoning his breeches with the other hand.

“A man who lives at sea must, in the end, gratify himself however he can.” He shoved a hand into my skirts but was frustrated by my elastic stockings. “I don’t expect you to sympathize. What does an old hag know of the needs of men?”

“Carles,” I croaked. “I am an old woman. I have buried two children. I have little left in this world. Take mercy on a woman your mother’s age.”

“Maybe you should speak less and work harder at getting out of your damned skirts,” he said, his hand still groping.

“Sir, my daughters, Casia and Aleja. Casia was five. Dark hair, sweet dark eyes. Always brown from playing in the fields.”

“Shut up and undress, Darra.”

He was in no hurry in spite of his words. And he was enjoying my pleas. They fueled his wicked intent further. A sick man.

“She died in my arms, sir. Five years old. Have mercy. Died of the fever before her life began.”

Carles shoved me to the ground, hard. I skidded painfully against the short pile of a Turkish rug. My elbow burned at the rub of the fibers.

“I would do anything to have them back,” I said to no one, for Carles was preoccupied with tearing off the remnants of my stockings.

He laid his full weight on me as he fumbled in his breeches. My small ribs bent painfully inwards. I lay shielding my face, my thoughts tangled in another life, one where I had my babies and their playtime shouts filled a small room in our shared house in Malaga.

“Darra! Darra!” A mighty little voice broke the ungodly tension, followed by a clattering. I craned my neck to find the little peddler waiting in the sharp shadow of the building, upon her tricycle. The wooden horse stood frozen just over the doorsill.

Carles sprang back, hands cupping his half-exposed cock.

“God in Heaven! Sorcery!”

His reaction surprised me. I scrambled to my feet, covering myself, and found him staring wide-eyed at the urchin.

“You spooky fucking witch, muttering about the dead, summoning a kid to save you from what you had coming,” Carles babbled. Then I knew how to seize on his guilt-ridden hysteria.

“Casia, come to mother,” I said in Spanish, arms out to Nur. “Come, little one.”

Nur scrunched her brow, uncomprehending, but my words were enough to send Carles vaulting over the tricycle horse, his eyes glued to my small rescuer the whole time.

“Supersticioso,” I groaned to Nur, stepping over my shredded stockings and touching each of my sore ribs. My heart was racing with the fear I had swallowed.

The tricycle came rattling fully into the room. Nur had fashioned a whole stowing system between the two back wheels. It could carry not only a coffee pot, but the whole assortment of wares and the tower of ceramic cups, secured with some filthy looking netting and a sponge. The child would make a resourceful sailor.

I decided the second pair of socks didn’t need ribbing after all.

I held out the gift to Nur, ashamed of my deep gratitude. Why should a small child have to save me from a man like Carles? Why should anyone have to save me from the decay of my life?

Nur stood from the tricycle seat and took the freshly knit socks. I pointed down at her slippers and their lonely few sequins, pitiful as featherless birds.

“Aaah,” came her response. She shuffled out of the slippers and pulled on a pair of socks, the ones made with good French yarn dyed plum-colored with bilberry juice. Nur bounded up and ran a joyful circuit of the small chamber in her new socks. Then she sat back down and pulled on the second pair on top of the first.

The spectacle cheered me, though my life had drifted so far out to sea, a fleck of flotsam upon the waves.

• • •

Curiosity and restlessness mingled with a fear of rebuke until I decided to seek out the captain. I imagined the heap of clothes building in the corner as the captain cursed my truancy, and the richly patterned rugs of my otherwise barren room held less and less of my interest with each passing day.

At a whim I headed in the direction opposite the short path to the toilets. It was midday. I clutched my sewing kit under my armpit, an explanation for myself, for my wandering. Rows on rows of Ottoman style lodgings identical to mine crowded along pebbled paths, their unfinished ochre bricks sandwiched together with thick, untidy coats of mortar. The disorienting repetition under the beating sun tightened my lungs.

We shared the quarantine compound with several crews, judging by the number of longboats, no two alike, which had been moored along the lazaretto’s promontory when we arrived.

With all its temporary inhabitants, the compound was a quiet place by day. At night card games sprung up around firepits and doors were left open. Once or twice I had heard the commotion of a midnight swim, big splashes as hooting sailors jumped off jutting rocks and into the black sea. But I had not seen nor heard any familiar sailors among the revelers of the night.

I wondered how I would find the captain — especially when it seemed that the crew of the Tridente were making efforts not to be found.

I turned corners until I had all but lost my bearings in that maze of lodgings. When I began to follow the sound of the ocean, hoping to reorient myself by the coastline, another sound captured my ears.

Hanging in the heavy, waterlogged atmosphere was the susurrus of animals. As I approached I recognized it as the wheezing and agitated neighing of horses.

Then a terrible smell struck me, a cloying stench as of a half-spoilt egg sitting in a platter of raw meat in the sun. I came upon the source: a courtyard scene of commotion, and three unsettled horses on reins held by Turkish guards. Several others, their heads tarbooshed or bare, gathered around a bloodied, battered human body. Blotches of red hoofprints stained the pebbled earth. The smell enveloped me, carried on tendrils of heat shimmering in the bright-lit court.

I ventured closer, my apron bunched up before my nose. In the remains of a face caved in by a hoof-sized crater I recognized Rafael, a rigsman who had joined the Tridente’s crew right before the start of our previous voyage. He had been trampled completely, in places nearly flattened, doused in blood. My thoughts turned immediately to murder, for an accident of fate, even involving a stampede of three horses, could not have so completely destroyed a man’s body. I thought again about the anxious whispering on board our ship, and our delay making port at Beyrouth.

“Darra! Get back to your room! Nobody called for you.” It was the captain, his voice muffled by the thick ball of cloth held to his face. Despite the heat, he was dressed formally in tailed longcoat and breeches. I was close enough as he turned to me to see that the whites of his eyes were gummied and pink. He was drenched in sweat.

Before bowing my head to the captain, I scanned the scowling faces of the gathered Tridente crewmen: Morizio, the African oarsman Abau, Vasco, Carles, red-haired Hermann. Their eyes wept, whether in sickness or grief I could not tell, and they sweated through heavy garments otherwise reserved for winter.

“Are you hard of hearing, you ox? Get away from here!” said Carles, and stooping to pick up a pebble, lobbed it at me.

It struck my knuckle, but I scarcely felt it. I was thinking about something else as I backed away: the oddness of the putrid smell that forced hands and handkerchiefs to faces — that it didn’t smell like the death poor Rafael had been dealt. His body was fresh, the blood still dripping; the flies that overran this part of the world had not yet discovered his corpse.

And as I took a final good look at Rafael in death, I saw something that rattled my bones. On the underside of his left arm, tucked under his body — the only part of his corpse both unscathed and stripped bare of clothing—three pustules bulged, the skin above them taut, livid, cracked, each the size of a thumb.

A fourth had cracked open outright. From the burst, ragged skin seeped mucus. It had trickled into the sun and cooked upon the sun-warmed ground. No one else seemed to see these small wounds in the shadows while Rafael’s fatal wounds shone in the light, but the residue leaking onto the stony ground was impossible to mistake.

The stench wasn’t like eggs — it was eggs. Growing under Rafael’s skin.

• • •

When Rafael’s infested corpse flashed like an afterimage of the sun behind my eyes, memories of Casia and Aleja followed. Not the sweet memories, but the world-ending ones, of Casia’s limp body wrapped in a dirty tarp, thin and yellowed, bloody tear tracks marring her round cheeks. Little Aleja holding my hand tight as masked men, trailing incense, lay her sister onto a pile of the dead, our Casia so much smaller than the others, her little feet hanging free, nubs of toes still perfect even in death. And the shivers of fever already wracking Aleja’s small limbs as the horses trotted out, carting my firstborn off to a common grave.

“Darra!” came the child’s insistent shout through the door. I opened it to find the little urchin on foot, overflowing with more wares than ever, weighed down like an orange tree before harvest. The coffee pot was strapped across her back in addition to her usual encumberments, and the broken front wheel of her tricycle dangled from the crook of her elbow, sharing this mooring point with the usual water bladder. Kohled eyes shone up at me. Spittle streaked a quivering upper lip. She looked miserable.

“What happened? Where’s your tricycle?” I asked, making pedaling motions with my palms.

When my meaning dawned on her, the little urchin’s face contorted tearily, until she no longer seemed older than her handful of years. In that earthy voice she began to babble some explanation. I could hardly tell her sobs apart from the words of the native language, but I knew well how to comfort a small child.

I gently helped her spread out the goods she carried on the bed, and brought out my box of buttons to soothe her. But the small peddler was inconsolable, and once her arms were free I saw the recent marks of a stick or a cane welted across her skin, shoulder to elbow.

I held up the detached tricycle wheel, suddenly fearing for us both. “What happened?” I asked again, pointing at the wheel.

This time Nur dropped to silence, then, resolving something, motioned for me to follow behind. I went along, chasing tiny plum-colored socks stuffed into threadbare sequined slippers back into the maze of the lazaretto.

• • •

And then we were in Nur’s own place; blankets heaped in the dust, the untouched second pair of socks, and a red felt tarboosh, a furrowed slash through it as though it had been caught on something jagged. In the corner, beside a pillow so thin it could have been a handkerchief, was a heavy-looking tobacco pipe I guessed was stolen, and a pile of marbles on top of a nest of cloth.

Nur poked her nose behind the nearest stack of crates and withdrew two oriental swords.

The rust-speckled blades were slender, curving towards the little urchin as she held them one in each hand. They were too small and easily wielded to be anything but a plaything, but she held one out to me, repeating her refrain of “Darra! Darra!” in her too-deep voice, and then eastern words flew out of her like loose stones tumbling down the side of a Lebanese mountain.

The sword was the first one I had ever held. When Nur put it in my hand, I thought of the weight of my only bronze stockpot hoisted down from a rafter, how Casia would help me fill it from the well and walk it carefully back to the kitchen. She would watch me boil the lentils we had spent the morning clearing of stones and dust and mildew. We added meat spices at the end, to pretend we were eating that morning’s catch of shellfish, fresh bread, a ragout of spiced sausage. A dish of eggs and peppers, golden yolks running to the edges of the bowl.

I thought of dead Rafael, seeping secretly in the courtyard.

The little urchin did not test her own sword like a playful youngster might. She held it solemnly, her purpose too deep and heavy to sparkle in those long-lashed eyes. The recent welts on her arm had begun to bruise purple. With her free hand she took mine and tugged me towards the door. I steadied my nerves with one extended breath.

We went.

• • •

I had a better clue: the muffled sounds of clipped Spanish through the door. “Bring him over, Vasco…”, “Here, here.” Accustomed to hearing words through closed doors, or flung over a shoulder on the wind, I noted the tension in the captain’s voice. It inflamed my dread. Nur had quieted down, her urchin’s fingers spidering to hook the metal ring hanging from the sculpted door knob, her feet in socks and slippers bracing to pull the door open.

I put my empty hand over Nur’s on the metal warmed by the humidity and heat of the late afternoon, and stepped between her and the door. I was clenching my jaw, the chewing teeth I still had aching, the gummy voids in between throbbing with pressure. When I pulled at the door it gave smoothly, no latch to hold it fast.

A burning bonfire where the bed should have been threw jittering shadows on the walls, and cast angular light on a handful of sailors.

There was a moment of complete calm as the door swung open, while eyes adjusted theirs to the sun behind us, ours to the fire and smoke. That awful smell hung, cloying, even with the thick woodsmoke coughing out through the seaside window. Then shouting cascaded, Nur angry and guttural behind me, the sailors indignant, concerned, outraged.

“It’s the fucking seamstress, captain,” said Carles.

“Shit,” said Vasco.

“What are you doing here, you? Have you no scrap of instinct for when to keep to yourself?” The captain sounded incensed, angrier than I had ever heard him, angrier than he ever was when gales battered the Tridente and the crew grew tired of jumping to his commands. But the anger masked a hoarseness of voice, a struggle for breath.

“Who will explain what happened to Rafael?” I asked, directing my question at the captain. “And this child was caned by our crew. Is that how vicious we’ve become?”

I stroked Nur’s hair. It was thick and knotted as a broom bush. At my touch her mighty voice burst anew; she shouted and gestured at the fire, craning up at me. It took me too long to recognize what should have been obvious, but even my wilted mind could not mistake the wooden horse gnawed by fire, the ornate curved lengths of metal being heated to a red glow by Vasco and Carles.

“You made kindling of her tricycle!” I was devastated, heartbroken, and I could not say why.

“Tricycle! Rafael! A half-grown savage at your heels! Darra, you know nothing! Nothing!” the captain roared. “You want to know? Is that right?” He strode to Morizio, who was slumped against the wall at the opposite side of the bonfire. “Look at this man!” The captain grabbed him by the tunic, yanking it roughly upwards as Morizio writhed. The sailor struggled to free himself of the shirt as though it were doused in acid, his agonized shrieks cutting the thick, diseased atmosphere.

“Look what afflicts us, by God!”

The shirt came loose and I saw.

Tens of bulbous, festering pustules, each taut and egg-shaped. No, not all egg-shaped, for some had been crushed by the captain’s cruel undressing. They oozed yolk and pus and blood down into the cleft of Morizio’s bellybutton. Dotted among the pustules were shiny wounds like wax seals, angry and puckered. Wounds made by a cautery rod, like the fire-heated metal frame of a tricycle. By desperate men.

I dropped my toy sword, overwhelmed.

I had mopped up black vomit from the smooth hollow of Aleja’s chest, her skin yellow as a maize field, her inhalations too weak to replenish her lungs. I had already lost my elder girl then. I remembered rubbing my eyes with the backs of my hands; I had wanted to catch it, to go with my daughters to wherever innocent girls were allowed to laugh and play forever. When I realized I could not follow, joining the Tridente’s crew — living in my own Hell — had seemed easier than continuing our life without them.

Morizio coughed past a web of phlegm in his throat, and I was filled with sudden revulsion. I did not want to die like this. I was not one of these men, with their vices and their hard hands and their loveless lives.

“Fuck her and that little monkey that follows her around,” said Carles, turning away, towards Morizio. “We have bigger problems, captain. Hold him down, will you, Vasco?”

Vasco held Morizio. Carles readied the red hot poker. I tugged Nur towards the door.

“Come, little one.” It was not too late to save her from this wretched room, its infectious fumes. Morizio screamed and thrashed as the sizzling poker met one of its marks. I tugged on Nur’s hand again.

The urchin broke suddenly free and ran at the fire. She began swatting the burning horse with her sword, nudging it out of the flames. Resolve set her face, her big eyes reflecting twin bonfires.

“Get away from there, you! Psst!” said Vasco, turning to give Nur a small kick to the hip. She tumbled sideways, then regained her feet, and went back to rescuing the figurehead of her beloved tricycle.

“Why play so nice with a savage half-sex whore’s get?” said Carles. “At home we’d tie it to a post in the garden to make a living scarecrow, right Darra?” And he lifted the glowing poker he’d held to Morizio’s pustules and sent it arcing towards Nur’s bare shoulders.

And my body erupted with a searing, silver pain as wide and borderless as the ocean. I must have run forward, for the poker landed along my arm and collarbone and neck, a line of fire. I had been hit by a bolt of lightning, doused by an up-ended volcano. I wished the person who was screaming so frightfully, so deafeningly, would stop, though part of me knew that the voice was my own. To escape the odor of cooking flesh I buried my face beneath my armpit, and a tiny body shouted “Darra!” against my skirts.

“Oh well, Darra,” Carles’ voice taunted, far, far away. “You’d probably caught the eggs off one of us already, we’ve all used you enough times.”

I remember a rectangle of light widening as the door opened onto the dusty alleys of the lazaretto, then a netting of humidity descending on me as I ran half-conscious, ears roaring, behind the scampering child.

• • •

I remember Nur arranging a Syrian veiled garment on me. I remember feeling icy shivers radiating from my innermost parts outwards, and how I gathered the mildew smelling robe tighter for warmth, though the air was drenched with humidity.

Nur guided me while I became almost senseless with the throbbing of my wound. I had visions of a Syrian mountain beast sinking its enormous jaws into my collarbone then shaking me to free a bite of rancid flesh. While these waking nightmares filled my thoughts, Nur dragged me by the hand, first concealing us in the shaded alleys of the lazaretto, then leading me to the entrance of the quarantine compound by way of the shadows of the lodgings along the lazaretto’s coast.

At the entrance, we encountered the stone-faced, tarbooshed Turkish guard who had chaperoned the Tridente’s crew into the lazaretto weeks ago. Nur wrapped a spindly arm around my hip and spoke to the guard for long minutes while I peered out from within my Syrian robes. I realized then why Nur had earlier removed my canvas espadrilles, unknown to these shores. Could I pass for the child’s relative? A supplier of coffee, a confectioner of boiled sweets?

The guard twirled his waxed moustache as he interrogated the little urchin. I willed him to look away from my uncovered eyes and the dark secrets etched so clearly upon them.

Suddenly the guard’s rolling thumb and forefinger stilled and he locked hooded eyes on mine. I cannot say with certainty, but it seemed that he had found me out, for recognition washed his features. But in the next moment he swung wide the gate of the lazaretto, granting Nur and I leave to enter the city of Beyrouth. Whether it was pity or trust that moved him, I did not know.

The city opened to us willingly. Two new furtive faces were nothing amidst the bustle we found in the central square. The smells of spice, sweat, and tobacco layered on the cacophony of colors to unsettle me and churn my stomach. Turbans, billowing slacks, tarbooshes, curl-toed sandals, robes, and conical hats trailing gauze adorned the dark-featured Syrians and Turks. The evening crowds of Beyrouth swept past. Some led donkeys or haggled in the night market. I let myself be moved along until I no longer saw Carles’ vicious face pursuing me in the night. Then I broke free of our flight from the lazaretto to sink down in a quiet corner behind the street face of a mosque.

The little seller retreated a while, but returned to me carrying a bowl of water and a rag. “Darra!” she repeated to alert me as she bathed my burns. Had I the strength I would have sent her away from the contagion rooting itself in my skin, but I was wracked with a deep chill once again, too weak to resist.

Instead I allowed myself to walk the streets of Malaga hand in hand with my Casia and Aleja. Each time the scents of Beyrouth intruded I covered my nose more tightly with my musky veil. And when the horrors of what might have infested my body threatened to unravel my mind, I looked upon my clever-eyed little seller surrounded by her untamed city and put my back to the wall inside me, stalwart and straight.