The Many Names of Eels

by Laila Amado

4327 words

© 2023 Laila Amado

When the mad emperor sought to defy land and its traditions, he dared to build this city on the shifting, heaving waters of the ancient littoral swamps. They’re still here. Beneath the shell of granite and concrete, dark currents whisper.

I go with the flow of the wide central avenue, trail the tip of my finger along the cool expanse of a polished, fog-colored wall of a building on my left. A lot of time passed since I last walked these streets.

The city rises upwards — its arches, balconies, and the capitals of columns reaching for the sky. Here and there, among the alabaster lions and the bronze hippogriffs, glossy advertisements on the ancient facades shine with the bizarre colors of a neon rainbow.

Crowded tour boats dart back and forth on the canals, lifting plumes of moss-green muck from the sediment murk of their bottoms. Camera shutters go off, and off, and off. Mouths agape, weekend visitors stare at the sad faces of marble angels holding up the bridges.

My sister thought that this newly-found enthusiasm for our city was endearing. I thought that it was disturbing. We fought about it. I chose to leave and wasn’t planning to come back, not until I received that letter. I can clearly see it in my mind’s eye, a thin gray envelope falling through the mail slot. The kind of gray that sucks in light. The kind of gray favored by the sky over this city.

I cross yet another bridge. To a lonely gull flying above, this city is a lattice of steel and silver ribbons. Locked in their granite beds, canals break the city apart — district by district — and bind it back together into a singular body of an estuary falling into the northern sea. There’s more water here than land, above and below. I pat the wrought iron tentacle spiraling at the end of the guard rail as I step off the bridge and leave the central avenues with their postcard views behind.

Here, the buildings are more humble — pitted brick and ocher paint, rather than marble and weathered bronze. Chimney soot stains the beautiful faces of hoofed caryatids shouldering the roofs, ash runs from their hollow eyes in rivulets of black tears.

These streets are old. Tourists have no idea, but those of us born of the swamp know that beneath the brick and mortar apartment blocks, stilts plunge into darkness, into the primordial depths where the shoals of pale fish roam in the cold pitch-black water.

I dive deeper into the familiar intersections of these streets, take in the faded decaying allure of the neighborhood. The air smells of salt. My legs carry me forward with the ease of a local, as if I had never left. One turn, another, and the house rises in front of me; rusted water pipes and mollusk shells running up its walls. I check the address scribbled on a piece of paper. I have arrived. I wish it had never came to this.

Above me, the sky is a heavy leaden blue. Looking up into it feels like peering through water at the bottom of the sea. Even on a good day when one’s eyes are not swimming with sudden and unwelcome tears.

There was a sea here once. Not the one breathing just beyond these streets, an ancient sea that came before everything else. It never went away, not really, regardless of claims in textbooks printed inland. This city stands in the benthic darkness of the ancient Littorina Sea. If I squint, I can see them — the diaphanous dorsal fins, the armored plates, the sharp rays and spines; all the transparent bodies of spectral fish floating through the doors and windows, circling antennas on the rooftops. This city is a ghost dwelling at the bottom of a ghost sea. I wipe the corners of my eyes dry and push the door open.

• • •

The apartment I’m looking for is on the sixth floor. The door is a deep russet red, the color of wine gone sour. Paint once applied with a generous brush has run down the wooden panel and frozen in droplets like amber sap on a pine bark. A cluster of doorbells smudged with the same paint nests beside the door. Eight in total.

I thought such overcrowded labyrinths of communal apartments went extinct when I was still a child, but here it is in front of me. I find the correct bell and press the button. Shrill ringing erupts behind the door, followed by deafening silence.

The echo is still vibrating in my ears, when heavy iron bolts slide aside and the door opens. A woman dressed in a faded blue dress with a white apron tied across her waist stands in the doorway. Graying hair without a touch of dye tucked behind her ears, she can be forty years old or four-hundred. It is impossible to tell.

“I’m here to see the diviner, I say.

She looks me up and down. “Lost something?” she asks.

“Someone,” I answer.

She nods and gestures for me inside. I step over the threshold. The apartment smells of cabbage soup, floor wax, and faintly of seaweed. A narrow corridor begins at the door and leads deeper into the interior. Laundered linens hang from ropes strung across the ceiling and billow like sails. I cannot measure how long this corridor is and where it ends.

“She takes payment, you know,” says the woman.

“Yes, yes, of course.” I nod, opening my handbag. I know the rules. A wad of colorful banknotes passes into the woman’s hands, each from a different maritime nation, each having gone through fishermen’s hands. She counts them with diligence, index finger from between the tip of her tongue and the bills.

As I watch, mesmerized by the repetitive movement, something wet and slippery slides across my foot. The sensation is so unexpected and out of place on the sixth floor of an apartment building that I yelp.

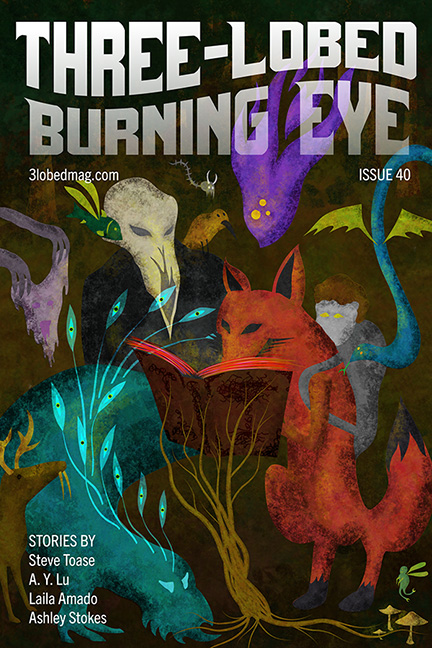

Slithering along the parquet floor of the corridor is an eel. Its serpentine body, brown with a silvery sheen, zigzags surprisingly fast across the slats. I stare in awe. I always thought that since the people from the new inland government had the dam built, that the migration patterns of the eels were irrevocably disrupted, and they no longer found their way into the canals of the city.

The woman turns and shouts over her shoulder. “The eels are escaping from the kitchen again, Mother! Didn’t I tell you to watch them?” No answer is forthcoming. She flings up her hands in frustration, stuffs the bills into the pocket of her apron.

“Go on.” She waves me on. “Fifth door on the left.” And then she vanishes behind the curtains of drying linens after the fleeing fish.

The corridor is bathed in silence. For a few moments I stand there, stunned by the sudden stillness, but I came here for a reason and cannot afford being overwhelmed by an uncanny feeling. I slide through the gap between two sheets and find myself in a labyrinth of billowing white and gray fabrics. The air smells of sea and iodine, and for a split second the floor surges beneath my feet as if I’m walking on the deck of a boat. I shake off a brief spell of nausea and press on.

The fifth door is white like all the others — chipped paint and a polished nickel handle. I raise my fist to knock and pause, when a clear voice calls from within, “Please do come in.” There is no use dawdling when the decision is already made. I push the door open and step into the room.

The diviner is sitting at a table. A thin gossamer veil the color of winter storm covers her face. Her hands with bulging blue veins under the paper-white skin, rest on a map spread before her. The printed paper is creased and stained. Pale outlines of city blocks severed by the network of canals, and I wonder how many come here searching for answers.

She gestures at the chair across from her and a dreary cold feeling grips me. It feels as if chilly wind from a hidden sea blows out of her extended fingers. Still, I owe my sister that much. On wooden legs I make my way to the indicated chair and sit.

“Tell me,” the diviner says, and her voice is a soft rasp of low tidal waves scraping against the quartz of littoral sands.

I expected it would be hard to talk, to share the dread of these past few weeks with a stranger, but the words spill from my mouth, unencumbered. I tell the diviner about my sister: the games we played, the stories we shared, the way we confused our reflections in the mirror when we were young. I tell her about the gray envelope tumbling through the letter slot in a town so many nautical miles away from here. About the words on the page, dry and detached, and about their meaning which I did not manage to grasp on the first reading, and had to reread the letter again and again. I’m not sure I understand the meaning of these words fully even now.

“Your sister is missing,” says the diviner and the mournful shrieks of gulls outside the window echo her words.

“Yes,” I whisper as quietly as I can, as if saying it out loud would make the reality of it more solid, more real than I can bear. “I need to know what happened to her.” I look into the diviner’s veiled face. “I cannot continue not knowing.”

This is why I came here today, why I walked up these stairs, and rang this bell and entered. I cannot go on not knowing what happened to my sister. We had our differences and we argued bitterly over what we thought was best for this city and for our own lives. I wanted to move away from the ghosts and the moaning waves. She wanted to help the city step into the future, thrive in the bright new world. I did not view that world as a good thing and could not imagine this city’s place in it. But all disagreements aside, she was my sister.

Gray envelope clutched in my hand, I traveled back to the city I never meant to see again. On the train and the boat, I tried to pretend that the handwritten words were not real. It was a terrible misunderstanding, I thought. I kept clinging to this hope as I walked from the port following a well-remembered route, ascended the stairs of the house where we grew up, turned my key in the door, and found the apartment empty. Nothing but silence and dust. She was gone.

I asked the neighbors, but they knew nothing, sad faces folding like paper darts at my approach. The police, the registry, the city hall — all turned me away. They weren’t even looking for her. The people in these offices with their sleek hair and expensive suits, I’ve never seen any of them before. Eyes the color of copper coins, they came to the city of canals and bridges from the new capital, up on the inland hills. Up away from the sea, they must have run out of vacant positions. So, they came here to exercise power. Wherever I inquired, they turned me away. These newcomers have no understanding of this city, don’t know the history of the swamp dwellers, but they know how to shut the doors in our faces.

“Let’s see,” the diviner says. From a battered tin box she takes a small bundle of colorless cloth. Nestled in the fabric lies a small brick of brown bread, the darkest rye. I know enough not to inquire about its origins. None of the swamp dwellers would. We recognize the bread of our dead when we see it.

The diviner’s pale fingers pinch off a small portion. In her hands, the dry bread breaks into a dozen large crumbs. She blows on her fingers, the edge of the veil rippling like the bell of a jellyfish, and the crumbs slide from her palms and roll across the city map.

A keening sound akin to a wounded seabird’s cry escapes her lips as dark droplets of blood begin to pool around the crumbs. They swell into pools and then spill, running across the map in rivulets, intertwining to form a strange symbol centered around the intersection of three canals. I know this place, but the meaning of the blood-painted sigil eludes me.

“What it is it?” I ask, my vocal cords pinched with dread. “What does it mean? Tell me what happened to my sister.”

“Let me show you,” the diviner says. Her cool pale fingers clasp my wrist, and the world tumbles into darkness.

When the curtain of shadows lifts from my vision, I’m no longer sitting at the table in the diviner’s room. In front of me is a richly decorated ballroom of a grand mansion, decorated with embossed gold wallpaper panels and crystal chandeliers. They’re all here — the new mayor and his wife, the judge and the police commissioner, the famous broadcasters and actors whose pictures smile from every billboard. Raised glasses clink. Bright light plays on diamond rings and expensive watches, shines on the perfectly white teeth.

The sound of the gong resonates against the walls and excited chatter rushes through the assembly. They file through tall mahogany doors at the end of the hall and into a dining room, where a table is set in the most peculiar fashion — red candles dripping wax at every joint of a sprawling cryptogram etched into the tabletop, each set of plates occupying its own cell of the pattern. There is something deeply disturbing about the arrangement and I feel a wave of biliousness coming over me, but cannot force myself to look away.

The gong calls again and the doors at the back of the dining room swing open. Footmen liveried in black and white, waltz inside carrying dishes on silver salvers. One platter lands in its designated cell on the cryptogram, then another; and I stare in horror at the steam rising from the pieces of flesh on the plates — the shanks, the joints, the human hands. So many hands.

As I hover, suspended in the middle of this abhorrent spectacle, unable to flee or cover my eyes, I see a portly servant in crimson gloves place the centerpiece dish at the intersection of the cryptogram’s heart lines — a round salver covered with a domed silver lid.

A violent scream rips from my throat tearing it raw, but no sound disturbs the silence of the scene playing out in front of me. Even before the man lifts the lid, I know what I’m going to see — and yet, the shock of it leaves me heaving and whimpering like a wounded creature. The dish is unveiled and I stare into my sister’s face, dead and bloated, a stuffed olive fitted between her darkened teeth. Bile rises in my throat and then a sudden darkness obliterates everything. I come to my senses gasping and crying in a chair in the diviner’s room.

“What have they done to her?” I wail, snot and tears clogging my throat. “What are they doing with all these people?” The image of hands stacked on the silver platters burns the behind my eyes.

The diviner is silent for a long time, still like a marble statue, and I begin to think she’ll never respond. The room lies in utter silence save the frenetic drumbeat of my heart. When she answers, her voice is no more than an echo of the winds blowing across some faraway sea.

“They want power, child,” she says. The confusion I feel must have shown on my face and she elaborates. “They strive to harness the ancient power of the Littorina sea, to thrust its magic on the cogs of their steel mills and printing presses. They consume the flesh of swamp dwellers, the true children of the ghost waters, to absorb the essence that doesn’t belong to them. If they imbibe enough, nothing will stop them from polluting the world with their corruption.”

She says no more. Anger—not the hot kind they sing about in the summer lands, but the cold fury of ice-laden waves beating against the granite shores in the midst of winter — rises in my chest and dries up the tears. I slap my trembling hand on the tabletop, scattering the breadcrumbs. The diviner gazes heavily from behind the veil, and I think she truly sees me for the first time. “I have to stop this,” I say. “Can you help me?”

“These things come at a cost,” she says, words coming out slow and dry like thin cracks breaking the ice while crossing a frozen river.

A shiver runs down my spine but there is no turning back now. “I will pay,” I say. “Tell me the price.”

“For you, swamp dweller, it will be the cost of one promise,” she says, and she lifts the veil. Her face is ageless, devoid of all color. I cannot help but stare at the opaque milk white irises of her eyes. From the folds of her wide sleeves, she extracts a small object — a matchbox covered in serpentine inky script.

“Promise me, that when the time comes you will not hold back the sea,” the diviner says. Water spills from her mouth and runs down the front of her neck, leaving a trail of salt crystals.

“I promise.” The words come easy. A strange calmness settles over me when she presses the tiny matchbox into my palm.

• • •

The wind and the waves don’t scare me. When I was little, they were the ones singing lullabies over my crib. Matchbox clutched in my fist, I hurry toward the area of the city where the buildings lean low over dark green water. In the distance, I can see the three canals converge, forming a knot between the park, the court, and the opera house.

I approach the balustrade flanking the canal closest to me. The tails of the bronze mermaids holding up the railing are green with age. To my right, algae-covered steps lead down to the level of the tide. In this weather, the stairwells descending to the water are deserted — no lovers hiding from onlookers, no poets sharing a bottle of cheap brandy. I descend unnoticed.

Locked within the walls of granite, the canal swells and rumbles. Water rolls over the stairwell’s submerged lower steps, the sleek and slippery stone blocks disappear into the murky darkness. Further along, at the intersection of the canals, the mayor’s mansion is bright with festive illumination, strings of yellow bulbs decorating its columns and balconies. Reflected in the black oily waves below, they flutter like bizarre underwater fireflies.

The wind picks up speed, pushing the waves upstream. In the distance I can feel the sea straining against the dam. The tall green wall of water pushes against the boundary in its path, rising up to the sky. It swarms with the silver darts of Sparling fish, puckers with the suction discs of lamprey mouths, teems with the intertwined bodies of the eels. I know their names, all the wet and slippery syllables.

When the big people from the new inland government came here to build their tidal dam, they told us it was to protect the city from the sea, but I’m no longer sure who and what is being protected. This city and the sea cannot be kept apart.

I unwrap my fingers from the matchbox clutched in my fist and slide it open. Inside, on a bed of cotton wool, rests a sharp triangle of a fish jaw, its narrow incisors and round molars uncannily human. I place it in my mouth and jump into the roiling waves. The water swallows me whole.

• • •

I become water. I flow with the cold dark currents rolling in the benthal darkness of the canals. Speeding past the broken bottles, the wheel spokes, the anchors and coins, the white skeletons — human and not so much. I become the canal and the fish, the sea and the city, nothing and everything.

The mayor’s mansion is a beacon, oozing rot and death into the water. Part of me wonders how those walking the streets above do not notice the corruption spreading from its stately walls.

Beneath the mansion’s grand facade, the iron grate of a culvert lies broken. I stream up its channel, strain through the cracks into the narrow water pipes, bubble up their twists and joints, spill from the copper faucet in a guest bathroom on the ground floor, and rise to my feet. Music, the mellow notes of jazz, echoes from somewhere above. I trail after the sound, leaving wet footprints on expensive carpets. This is how the first of them finds me.

Teetering on high heels, she follows the offensive dirty stains and sees me — sodden clothes, hair dripping wet — standing in a doorway. She regards me with an almost comic hauteur. I give her a sheepish smile, and in response she grants me a look of pure disdain, her small nose wrinkling as if she has come upon a pile of trash.

My smile grows broader and broader, impossibly so; and when she sees my row upon row of long cruel teeth, she has the decency to run. She doesn’t make it far. Blood from her severed artery splashes across the white smooth wall like a macabre piece of modern art.

I find the rest of them in the sitting room — thick fingers cradling brandy snifters, cigar smoke rising to the chandeliers. They laugh as I kick the door open, but the jokes die when I give them my smile, my whole mouth — a chainsaw of triangular sharp teeth.

Eager to eat the flesh of others, they never thought how soft their own; so easy to tear. Limb from limb, one loop of intestine from another. Blood streams across the polished floor, trickles into ventilation shafts, flows freely into the canals, washing away the rot.

When it’s all over, I descend the regal central staircase, push the doors open into the night. Cold breath of the northern sea spills over the city, stretches tendrils of white fog along the embankments. Now that those who killed my sister are dead, I should feel relief, but I don’t. There are other mansions, more predators in fancy suits carving their way to greater and greater power from the bones of my city, turning it into an empty hollowed shell. Is it even my city anymore?

The sea buzzes at the edge of my consciousness. Teeming with primordial life, it strains against the tidal dam. Its voice in my mind pleads to come home, asking me to let it in. I spit the fish jaw out into my palm and return it to the matchbox. I wash my face in the canal, and I walk away from the fading yellow lights of the empty mansion.

• • •

I drag my feet up the staircase, and in the empty apartment I climb into my sister’s bed. The blankets smell of sea moss and kelp, of the soft feathers white gull underbellies. I’m so tired, my bones feel like lead.

Closing my eyes, I let myself slip into the slow heavy currents of sleep. With every heartbeat I descend deeper and deeper into the luminous abyss of the Littoral Sea, until the gates of the tidal dam stand tall in front of me. The sea presses in on the other side.

I throw my arms wide in a welcoming embrace, calling the sea to come home. No gate can keep us apart. Somewhere beyond the city limits, sirens blare. When I wake tomorrow, there will be meters and meters of cold green water above me; salt, and ice, and writhing eels.