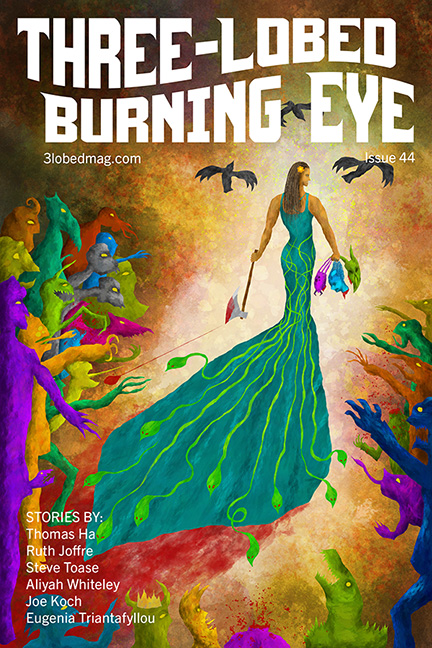

The Thing That Ate Itself

by Aliya Whiteley

3420 words

© 2025 Aliya Whiteley

Poppy dropped the letter on the coffee table, went to bed, stayed there.

She lay very still, curled up tight, hating her body for harboring them. There were microscopic images of them on the posters around town, part of an awareness campaign, reminding people to wash their hands; they were green, squashy balls peppered with twisted spikes. Floating around, sticking to her organs, sliding through her veins. A routine blood test had picked them up. There were no symptoms. She would have preferred it if she’d felt sick, weakened.

But the morning passed, and she found no sense of violation to hold on to. She realized it was possible to uncurl, to move, and not think of them moving too.

Many people had Cryptoidus. She had joined their number. It had first been identified a few years ago, spreading fast, origin unknown. A media campaign had claimed it would be the end of the world, and everybody had hidden in their houses, panicked. Strange, she thought, how shock and hate and fear are all conquered by long hours of boredom. Eventually everyone emerged, and life went on.

Poppy dozed the afternoon away, then woke feeling lightness and ease in her bones. In her dream, her mind had risen, freed from the grip of the invaded body, and she had seen herself from a height, as if looking down from the ceiling. A burst of love filled her for the small form beneath. If she couldn’t love herself, parasites and all, nobody else would.

She returned to work, telling a few people about her diagnosis. They shared theirs in return. It really wasn’t so unusual, anymore. Time passed. She wanted to belong to the world and its movements, and the green sticky balls could be part of her as long as she didn’t have to think about them, spinning through her veins and arteries, attaching and proliferating, and waiting.

• • •

“Hi,” said Poppy, as they arrived, even though they couldn’t hear her. “Lovely to see you.”

It was the start of a steady influx of cars, and she greeted each one in turn from the quiet interior of her own car. The sun was very low, dazzling; she flipped down the visor in the last red rays of the day. The drive-in was being held in the car park on the roof of a shopping center, the temporary screen erected against the backdrop of the sunset, and the cars turned the corner and swung up the ramp in orderly procession. The front row filled up quickly, then they began to park in rows behind. She felt a stab of disappointment at the uniformity of the cars — there were no convertibles, nothing old or eye-catching. So much gray. Not like the picture she had in her head at all. But why had she expected anything else? Didn’t people tend to make the same choices, want the same things? That realization made her feel even lonelier than before. She slumped back in the seat of her own dependable silver luxury sedan.

The heads. She tried to concentrate on the heads. Yes, that helped. She could read individuality into the small movements, the twists and shrugs. These people were having their own conversations. A couple in one car kept their heads close together. Kissing? Giggling at a shared joke? Another couple were sitting as far apart in their front seats as it was possible to get. An argument, no doubt. A man alone, one of the first to arrive, jerked his head back and forth; it took her a while to work out he was singing. She wondered what tune he was blasting out, then noticed the new message on the huge screen ahead:

Tune your radio 87.7FM

She followed the instruction, and the answer was revealed: one of those Motown hits, upbeat and catchy. His shoulders were moving in time to the music. Then Poppy caught the rhythm in other shoulders, and she watched with pleasure as people moved and sang along, down the rows: a choir that she couldn’t hear.

The cars kept coming.

They slotted into every available space as the familiar old hits were churned out. Who would have thought a reimagining of a monster movie would have been so popular? She had developed a love of creature features when she was young, with her parents working late most evenings and only the television for company. She’d done her homework every weeknight to the sound of low voices discussing disaster punctuated by the occasional outburst of mass destruction. A giant lizard flailing, or ants swarming over a screaming mass. Tonight’s film was a remake of one of her favorites, to the point where she felt oddly protective of it, as if it had been made for her alone. It was odd to think other people held it in affection too.

Perhaps the desire to recreate it was born in a boom of nostalgia, fueled by the era of problems they all lived in now. Politics, the climate, the parasites. Back then the monsters could be defeated.

The parasites are not monsters, she reminded herself. Just harmless passengers. At first Cryptoidus had been in the news every day, but years later it only warranted a small report every now and again. A spike in numbers, say. Nobody died and nobody got ill. What difference did it make?

The next upbeat tune started, and everyone sang along in silence some more.

The parking spaces next to her were taken, the cars slotted close, the doors nearly touching. Surely there was no more room in the lot, and yet still they arrived, squeezing into every available space, to the point that Poppy felt claustrophobic. She doubted her door would open, if needed. Leaving early was an impossibility.

“This film had better be good,” she warned the screen.

Talking to inanimate objects: another part of herself she had learned to live with.

The screen brightened. She had the sense that everyone’s attention was focused forward. The music cut off halfway through a song — yes, it was showtime. The familiar refrain of the studio bumper played through her speakers, followed by a burst of jangling chords as the title dominated the screen, and her attention was utterly sucked into:

The Thing

That Ate Itself

Breaking glass.

A single scream rings out.

Geoff sits bolt upright at his desk, his face a picture of concern. He leaps up, his shirt collar crisp, his sleeves rolled. He’s a handsome man.

‘Valerie!’ he calls. He runs out of his office, down the corridor, searching the rooms. He finds her in the library, looking through the window between two large cases filled with scientific tomes. Her shaking hands are pressed to her mouth.

He grasps her shoulders, turns her, and she sobs against his chest. ‘Valerie — what is it?’ He is tender with her, and he listens as her sobs subside. She manages to say, ‘Oh, Doctor Jackson — I thought I saw something. Over at the McCallister place.’

He frowns at the view. ‘What did you see?’

‘I don’t know. Something on the roof. I can’t explain it. Oh…’ She cries on him a little more, then steps back, embarrassed. ‘I’m so sorry, I…’

‘You’re tired. I’ve worked you far too hard this week.’

‘No, no, this is too important to stop, I…’ She checks her watch, then says, ‘We should get back to the laboratory. It’s nearly five o’clock.’

‘Yes, of course.’ He leads the way, and she follows, back down the corridor to the laboratory opposite his office. It is filled with long metal benches and scientific equipment. A large blackboard, at the front of the room, has numbers and symbols chalked all over it. They put on white lab coats from the hat stand by the door, and walk to the furthest bench. A small glass box sits atop it. Inside? A mottled green-brown blob, dull in color. It shifts. It pulsates.

‘No change,’ says Geoff. He smacks his fist on the bench. ‘Dammit.’

‘We just haven’t hit on the right formula yet,’ says Valerie. ‘We can’t give up. This is the most important discovery in the history of mankind. I just know it.’ Her eyes shine with determination.

‘Your enthusiasm is commendable,’ he says, ‘but we don’t really understand what this is yet. All we know is it was found in the bushes outside this very facility. How did it get there? Who put it there? I don’t like it, but I can’t refuse to investigate it. If only we could unlock its secrets.’

Valerie sighs.

‘I’m sorry,’ he says. That tenderness is back in his eyes, his voice. ‘You must have wanted more when you applied for this job. I’m a boring old fuddy-duddy, I’m sure.’

‘This is the best job I’ve ever had,’ she says. ‘If only — if only I didn’t have to go past that old house every day, or see it from the window. I can’t explain why it bothers me so much. I’ve begun to have nightmares about it.’

‘Is it the old legend?’ asks Geoff. ‘About mad old McCallister? I’m sure I’ve already told you that he was a perfectly ordinary man. Apart from being a great scientist, of course. He left all his money for the formation of this institute, you know.’

‘I know,’ she says, but she wraps her arms around herself, and shivers. ‘I know.’

‘They say the best way to get over a fear is to face it. Do you think you could do that?’

‘Maybe. If you were with me.’

‘Let’s go right now,’ says Geoff. ‘Don’t think about it. Just do it.’ He holds out his hand and she takes it. The blob in the glass box shudders, and shrinks away.

‘Look, Doctor Jackson,’ says Valerie. ‘It’s… in pain.’

‘It doesn’t have a nervous system, Valerie,’ he says. ‘It can’t feel anything. Can it?’ They both stare at the blob.

• • •

And yet this business of exactly reproducing the film did change it. It gave it an eerie feeling, distanced from itself and from reality. This felt like a copy of a copy, created by someone who only had the original movie rather than life itself to go on — as if they had only ever seen actors, and not human beings, at all.

And so it went on, over scenes she knew well, somehow made unfamiliar to her by the act of mimicry.

The old McCallister place, the looming black outline of it against an empty sky. The dilapidated porch and the squeaky floorboards as they step inside. The cobwebbed furniture, and the crow that suddenly flies from the rafters, followed by Valerie’s echoing scream.

Down to the basement, lit only by the beam of Geoff’s flashlight.

The dusty laboratory equipment, and in the center of the floor, a hole — no — a misremembering on her part — a tunnel, leading directly to the bushes by the institute.

It was strange, she reflected, how emotions change. When she had first seen this film it had scared her stupid; she’d spent nights awake, thinking every noise was the creeping of a green blob into her room, poking up through the floorboards. It was her fear that had drawn her back to watching it again, and again. She wanted to be familiar with it. Nobody can be scared of something they’re familiar with, she had reckoned. That’s like being scared of yourself.

But it seemed familiarity could not make her immune after all. It was getting to her again, just like it had when she was young. Even though she knew what came next, she found herself leaning forward on the steering wheel, involved in the action.

The handsome yet selfish grandson of McCallister turns up to renovate the old house, and Valerie falls for his slick charm. She overcomes her fear of the house and begins spending more and more time there. Geoff, lonely and bitter, sinks all his energy into working on the blob. It’s obviously one of McCallister’s experiments that managed to tunnel its way out of the laboratory, but what is it? He finds no answers but it thrives on his lone attention. It turns in on itself, over and over, and grows larger.

‘It’s... eating itself,’ Poppy says, in time with Geoff’s onscreen utterance.

McCallister’s grandson and Valerie, together, happy in that big house on the hill — all her fears forgotten. How can she be so fickle? All the while, Geoff’s loneliness consumes him. He never leaves the laboratory. Doesn’t shave, barely speaks.

The blob feeds on itself, devours itself. Grows bigger. Then, one night, it breaks free of its glass box as Geoff sleeps, slumped in a nearby chair. It flows around his feet, slithers to the window and out, to the bushes. It finds the tunnel and returns to the house.

A lone scream wakes Geoff. ‘Valerie!’ he calls. His gaze turns to the box, then the open window, and the house beyond.

• • •

He bursts into the laboratory, sees it revamped, filled with grotesque experiments. McCallister’s grandson has been busy, but now he lies on the floor, lifeless. The blob covers his face and upper body. It pulsates. It is a sickly, glowing green, with twisting spikes emerging through its mass, and it is swelling.

Valerie sobs on the far side of the laboratory. She holds out her hands, and Geoff carefully edges around the walls to her. They embrace. ‘He… he started talking about reviving the old ways of his family. He did terrible things down here, Geoff. He made me help him. He—’ She is overcome with emotion. He holds her.

The blob keens. It starts to shrink.

‘It’s in pain again,’ she says. ‘It… it can’t bear us touching.’ She hugs him closer, and it shrinks back further, and starts to lose its glow. ‘We can defeat it, Geoff, we can defeat it!’

Geoff pulls away. ‘I’m sorry, Valerie,’ he says.

‘What…? Why? Hold me, please hold me!’

The blob strengthens. It begins to turn over and over again, feeding on itself, growing.

‘Can’t you see how beautiful it is?’ Geoff says. He has eyes only for the blob. ‘I can’t harm it. I need it. I need to understand it.’

‘Geoff, no!’ Valerie looks from Geoff to the blob, then gives out a shriek of desperation and throws herself at the blob. It’s now big enough to swallow her head, her torso. It consumes her while her arms and feet thrash. It takes minutes. Eventually her limbs stop their wild drumming against the floor. The blob retreats, leaving her exposed skull, glowing green, the eye sockets hollowed white. Valerie next to the remains of her mad husband on the floor.

‘It’s eating us,’ says Geoff, with a vast smile on his face, his teeth very white, his eyes burning, alight with knowledge. ‘And it’s eating itself. We should all… eat… ourselves…’ He looks directly into the camera, lifts up his arm, and sinks his teeth into his flesh. The camera pulls back, out of the room, out of the house which glows green against the sky. The heavy, discordant strings of the orchestra ring out.

• • •

Poppy watched the credits roll.

Geoff and Valerie, together, defeating the thing that ate itself: that was what she had been expecting. A happy ending. What was wrong with happy endings?

People change, she thought, but so do films. They take on new meanings, new identities. The stranger they get, the more they reflect on the surface of reality, creating new distortions, drawing the eyes to what has been happening, over time, beneath what we think we know of the world.

The credits sped by.

Nobody left.

Car engines sat silent, no one pulled away.

She looked at the heads in front of her. They all faced forward, watching the screen. She risked a glance to her left. The man in the car beside her had his hands over his face. He was parked so close to her that she could see his short fingernails, bitten low. His shoulders jerked rhythmically, in time with the music over the credit sequence.

She turned to the right.

The two elderly women in that car were watching the names scroll past. Their expressions were emptied of meaning.

And the feeling came over her, all at once, that it was not her film, not anymore. It had not been made for her alone. It was talking to someone else, someone inside her. To many of them, all at once, and the cars wouldn’t start until the things inside were ready to be escorted away.

The credits ended and the screen faded to black: a moment without color, without depth. Then the first row of cars switched on their engines as one, and their brake lights punctuated the darkness with red. They pulled away one at a time, in order, evenly spaced at the same speed.

Poppy looked down, and found her own hand on the key in the ignition, ready to turn. But not yet, she thought. Something within her was feeding on what it had been shown. Commands had been given: to love herself, to be part of the crowd, to attend the screening. The perfect moment would come for… something. Some action. It would reveal itself to her. But not quite yet.

• • •

Who to tell? Poppy played it through in her mind. She could tell the people at work, the few she spoke to who might not think she was crazy. Share her suspicions online, or report it to her doctor, the NHS, the government. Start a petition. Demand to have the green blobs investigated, if that wasn’t already happening.

She could retrain as a scientist, and search for her own answers.

She could tell the world they were all in danger from these green blobs with twisted spikes, and fight them bravely, boldly. Lead a resistance. Be a hero. Have a film made about her. Get cheered in the street.

Her brain ticked idly on, listing realities and fantasies; and time passed, and she fell asleep.

In the morning, the memory of the remake had faded. She felt faintly silly. When she got to work she mentioned the film in conversation to her co-workers, and they hadn’t heard of the original movie.

“You should see it!” she said. “It’s a classic.”

But who had time for classics, really? Someone recommended a new TV drama to her, and she watched that for a while, mainly so she could talk about it with everyone. The drive-ins continued but she didn’t see anything that appealed to her. The memory of the remake of The Thing That Ate Itself faded, until all Poppy recalled was a vague sense of an ending that hadn’t quite worked for her.

There was meant to be a letter to ascertain the extent of her infection, but it didn’t arrive. Meanwhile, life went on.