The Bathers

by Eugenia Triantafyllou

6650 words

© 2025 Eugenia Triantafyllou

I call these women The Bathers because the beach was the first time I saw them for who they were. But you can find them anywhere. Or wait until they find you.

• • •

But my mom was not afraid of the ones who followed the unspoken rules, no matter how somber they looked. Those she understood well enough. They reminded her of her own mother, my yaya. Mother was wary of the other ones, the ones who stood out. Who wore bright-colored tunics with big red flower patterns during Sunday Mass, complete with matching lipstick, a set of oversized mother-of-pearl earrings, and elegant sandals showing off their well-manicured toenails. Most of them didn’t even attend Mass. They gathered outside in the yard after Service to eat prosforo—the sweet-scented bread the other churchgoers brought as an offer—to gossip and cackle with one another.

It was the cackling that got to my mom every time. “This is almost the house of God. Not a kafetéria.”

My mother would tsk-tsk under her breath. Some of these women shopped at our convenience store and she couldn’t afford to be rude to their faces.

“It is God’s yard.” I didn’t mean to sound glib. The women’s energy was pulling me in like a vortex and the more I stared at them the more distracted I became.

Miss Antigoni was the loudest of them and wore the most—according to my mother—garish clothes. In my eyes they were glamorous, from another age or a place that was better than here. Or at least less boring. At that moment Miss Antigoni lifted her eyes, shaded by her green trilby, and waved at us. The other women turned as one toward us.

My mother somehow managed to both glare at me and nod politely at the older women, whose precise age remained a mystery. Antigoni was supposed to be a little older than my yaya, and she had the wrinkles to prove it. But her hair was dark as coal and reflected the light like an oil slick (my mother half-joked she colored it with shoe dye). Her moves were tireless, her walking sinuous. Like a woman half her age.

“Poh poh, Maria!” said Miss Antigoni, showing a row of too-good teeth. “Your daughter is so grown. We missed seeing her at the store.”

She puckered her painted lips and did a mimicry of spitting on me to ward off the evil eye—thankfully without all the wet stuff that usually came with the gesture. I still recoiled, but my ever-watchful mother kept me in place by the shoulders.

“Katina has to stay home and study if she wants to go anywhere in life.”

Miss Antigoni broke into a fleeting laughter and waved us off. “That’s alright, Maria. Let the girl be.”

My mother relaxed her grip but only because she wanted to leave as soon as possible. She didn’t relax her smiling face though.

“We are in a hurry Miss Antigoni,” she mumbled apologetically. “See you at the store tomorrow for your newspaper and magazines.”

When we had put a couple of blocks between us and those women, my mom crossed herself and spit—for real this time—on her bosom.

“Why is she calling herself Miss? I bet she did away with her husband like your great aunt Vasiliki. You can ask yaya if you don’t believe me. That was her first husband, not the one she has now. But who knows for how long. If you keep not listening to me, you’ll end up like them.”

This didn’t sound like much of a threat to me. Miss Antigoni seemed to live a fuller life at seventy-five than I did at fourteen. I was never good with crowds. I did okay at one-on-one conversations—mostly with girls—especially when there was no one else around to steal the spotlight. But with groups of people, I was always overshadowed. My voice came out too low. My thoughts were half-formed and nonsensical. My jokes always ended at my own expense.

I did have one constant friend for most of my childhood, though. A boy named Dimitris, but we only saw each other in the summer at his parents’ tavern. Dimitris was fun and in love with the sea and all of its creatures. He taught me how to fish with only a fishing line, a hook, and some stale bread. Together we’d climb on the anchored motorboats by the jetty and take turns diving from the stern, or catch tasty limpets and sea urchins by the rocky outcrops. He had two older siblings who also helped out at the tavern. The oldest, Lukia, was three years older than us, but in our eyes, she already looked like an adult. She didn’t seem interested in playing with us or even hanging out. When she wasn’t working, she liked to embroider, sitting on a chair by the rocks overlooking the beach.

Then there was Vasilis. He was only two years older, but he was tall and big and every time I saw him, I walked away as fast as I could. It wasn’t that he was so different than wiry, baby-faced Dimitris that threw me off. Puberty had gotten to him faster than the other boys. It was that he was always mean and aggressive; and whenever he saw us playing together, he would find an excuse to call his brother to the restaurant and give him work. He would come up to me, chest puffed up like a rooster and push me out of the kitchen, saying I was just a noisy kid—though I was the same age as his brother. Whenever he was around our games would die out or he would take Dimitris away on some adventure where I wasn’t allowed. Dimitris never seemed to notice, or if he did, he never said anything to me; he was always happy to follow his big brother.

• • •

“Isn’t yaya going?” I asked. Hoping against hope that my grandmother would change her mind.

“Oh sure, your yaya is going,” huffed my mother while absentmindedly stacking potato chips on the shelves. Her face grew redder by the minute. “You know she needs her baths. But we are not. End of discussion.”

What my mother was too angry or ashamed to admit was that her sister-in-law didn’t want her there. I had pieced together what was happening from half-sentences that my mother and yaya whispered to each other and from what I knew about my aunt.

“She can’t explain it to her kids. Can you believe it?” my mother hissed while my yaya nodded. “What is there to explain?”

“Kids need their father, Maria. That’s all,” yaya said with a voice as non-judgmental as she could muster. But both my mother and I knew that she agreed with my aunt.

My father had left us two years ago for a woman I never met, and my mother never looked for him or begged him to come back. Never took another husband either. Instead, she took a business loan and opened the convenience store. She worked all day and night, stuffing shelf after shelf with potato chips, chocolate bars, magazines, comic books, bleach, and cat food. Everything that sold quickly, so we could get by.

Sweat came down my mother’s forehead. I rested my cheek against her plump arm until she paused stocking merchandise and passed her rough fingers through my curls. It calmed us both down.

“What do we need a vacation for anyway? Athens is better in the summer. Empty, no cars, clean air.” She turned to me abruptly and the movement gave my neck a rude awakening. “And you have to study for the finals. Don’t you think I forgot.”

My academic performance was anything but smooth sailing. I had failed Math and Physics and I had all summer to study for the repeat tests in September. My mother always deflected her anger and helplessness by trying to put me on the straight and narrow path. This sudden scolding wasn’t a surprise. It was annoying though.

Then came one of the hottest days of July. The ones that felt like I was wading through a fog of my own sweat. You can’t study when your brain feels like a moldy sponge. I must have looked miserable too, because the moment I stepped into the shop my mother barely looked up from the bills she was sorting, and said: You should take the bathers’ bus to Marathon.

The bathers’ bus was owned by an older woman and her son. When the first heat of the year arrived, the bus would make its usual route from downtown Athens to the nearest quiet beach. That was often the Marathon beach near the tavern Dimitris’s family owned. The bathers were mostly older people with their grandchildren and the odd younger couple with their toddlers. People who couldn’t spare the money to go on a real vacation, my mother used to say whenever we rode the bus together, back when my father was around and mom could take a few days off to spend some time with me. We’d arrive at the beach at noon and leave at night. We’d take a dip in the sea, then mom would sit at the tavern with the adults, sipping ouzo and tasting the catch of the day; and the kids would build sandcastles by the beach or dig traps and cover them with seaweed and reeds in the hopes that an unsuspected beachgoer would fall in. That’s how I met Dimitris when we were eight years old. I literally fell into his trap. He’d set it up in a weird spot, close to some rocks where the seaweed stank like an outhouse.

“I’ve been waiting for a whole week for someone to step in that,” he yelled from the tavern.

I saw the scrawny boy running toward me with a swollen belly and ears poking through his hair like two palm-sized sea shells.

“That’s not very nice,” I said, rubbing the side of my foot where a stone had cut me in the trap.

He stared at my bleeding foot but didn’t seem too concerned. “What were you doing here anyway?”

“I am trying to hide before my mom takes out the meatballs.”

“You don’t like meatballs?” That seemed to have shaken him a little.

“They’re okay but I want French fries.”

“Come to the kitchen. My sister can give you some and fix your foot.”

And just like that he became my summer friend. A friend I hadn’t seen for a couple of years. But now I was sitting at the back of the bus, wearing a yellow cotton dress and a baby blue one-piece bathing suit underneath, one with extra padding in the chest and wide straps to hold my recently expanded breasts in place. I was surrounded by three ten-year-old boys yelling at each other. Their thirty-something parents sat in front of us, pretending to nap so they wouldn’t have to deal with them. I looked around to see how many people I remembered. Two years wasn’t a long time ago but in my mind, they had stretched to a decade; and besides, mom was no longer by my side and people would surely ask questions. I would now have to act like an adult around these people even though I felt miles away from being one. To say I felt out of place would be an understatement. The parts that made me me felt mismatched. Body, and mind, and other people’s perception of me all blended to turn me into a Frankenstein creation of undeterminable age.

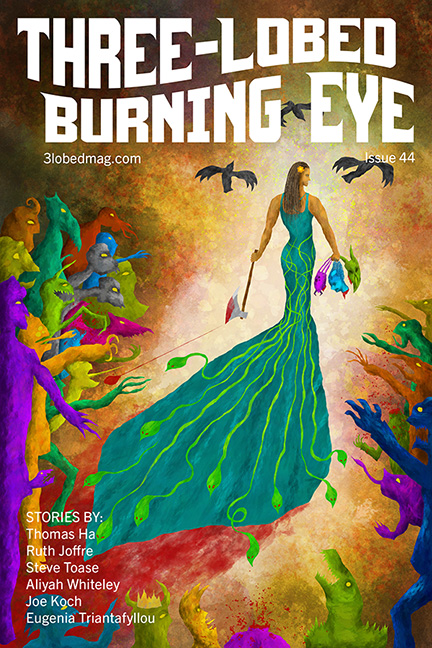

Then the bus door opened and The Bathers came in. Miss Antigoni and her three friends, Natasha, Melpomeni, and Aleka with their wide-brimmed hats and oversized sunglasses, their lipstick always flawless, and their heads held high. The whole bus went momentarily silent, even the three little devils stopped trying to murder each other and looked up. My mother had warned me before she finally let me on the bus: Do not talk to these women more than hello and goodbye. Do not eat any food they give you. Just say thank you and then throw it away when they can’t see you. Here, I packed some meatballs for you. You’ll be hungry after the swim. Don’t buy anything there, you know we can’t afford it.

But theirs were the few faces still familiar to me on that bus. I remembered a time when I was the annoying ten-year old sitting in the row behind Miss Antigoni on the way to the beach, pestering her about the big beautiful stones on her many rings. My mother was still weary of her and her company back then but she remained friendly and empathetic. Perhaps life had not hardened her too much yet. Perhaps she still believed women could be vastly different from her and still be good people.

The crowd began to steer again. It was Saturday and people were looking forward to Sunday’s rest and the opportunity to party. The driver turned up the nisiotika music and the bus filled with songs. People sang and lifted their arms to clap in the air. The atmosphere felt different since the group of women had arrived. Everyone seemed hypnotized by their presence, acting outside of normal.

One of the bathers, Melpomeni with the impeccable blond bob, opened a round tin box that once upon a time used to carry biscuits and offered carioca sweets to the children. When she reached me, she halted for a moment, as if trying to decide into which category I belonged. Here you go miss, she said at last, smiling wide. Give my love to your mother. I took the sweet, but instead of eating it I kept it in my hand, and felt the hardness of aluminum foil against my palm. I eyed the women who now occupied a full row of seats on either side of the aisle. There was one empty seat behind them, next to a man napping with sunglasses slipping nearly down to his mouth. Everybody felt at ease in the bus but me. I had no one close to me and I needed an anchor. I stood up, and, as quietly as I could, sat in the seat behind Natasha, whose fiery red hair competed for attention with the deep creases around her eyes.

“Thank you for the sweet,” I whispered between the seats. “Can I stay close to you for this trip? I don’t know anyone very well.”

“What’s wrong with you, girl?” Natasha turned her plump body around to look at me. Her wrinkles moved like a hypnotic spiral around two brown eyes. “You look so sad. You used to be such a happy little girl.”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. I am not little anymore.” I absently glanced at my breasts but they must have noticed.

“Too many sleazy men looking at you?” The voice came from Miss Antigoni who pretended to gaze at the view outside. “I have been there.”

Taken aback from her bluntness, I felt my face heating up. I must have been red as a poppy.

“Not just men. Everyone is looking.” My words came out at last. Low and weak, but honest.

“Looking and judging, eh? They love to do that.”

“The first forty years are the hard ones, girl. After that they stop noticing you little by little. By sixty you are invisible.”

There was high-pitched laughter from the seats on the right. Some people stopped clapping to the music.

“But that’s a good thing, you see? When they are not looking you can be anything you want. You are free,” Aleka, with her steadfast jaw and her wavy silver hair winked at me. She looked like a wolfish creature for a moment, her nose too long, her chin too sharp. I blinked and the vision was gone.

Miss Antigoni reached out a too long arm and patted me on the shoulder. “Don’t worry, dear. You can stay with us. We won’t tell your mother.”

• • •

“Katina?”

I nodded in awe of the person he had become. Dimitris looked almost like a twin of his older brother, and I felt both silly for being so surprised and betrayed when I realized I missed the last years of him being a boy. Or that’s what I imagined had happened. The first day of summer he woke two whole heads taller, like some fairytale curse. I assumed he thought the same about me and my newly expanding body, which he examined without embarrassment as I stood there, so much so that I nearly yelled at him to stop looking.

“Who’s that?” The familiar voice came from the kitchen, but what I saw wasn’t familiar at all. His brother Vasilis appeared, fully an adult. He wore a thin mustache that he was clearly very proud of, and left the top of his shirt unbuttoned in the hope that the few hairs that had grown on his chest would cause some sort of thrill.

The slight smile he had coming in slowly left his face when he realized who I was.

“You again? Aren’t you old enough to know not to be sneaking in the kitchen? Go on. Scat!”

He shooed me away even though I was not standing in the kitchen but among the empty tables and chairs of the dining area. I rushed out of the restaurant with my face burning from shame. The four women had already donned their flashy bathing suits, covering their eyes with big ’70s style sunglasses and their heads with swim caps. A few people glanced their way, but they quickly wrote them off as silly old ladies. Some older women though crossed themselves just like my mother had.

“These boys are no good,” Melpomeni clucked her tongue when she saw I was about to cry.

“I’m okay,” I told them, though no one had asked. They stood as still as the rocks behind them, staring at the boys for so long that I prayed for a trap big enough to help me disappear from the face of the earth.

“Let’s go swim,” Miss Antigoni said at last and that seemed to break the spell.

Older women didn’t stray too far from the shore. When I was younger, I remember laughing at the grannies who splashed in the shallow water because they looked to me like oversized toddlers. Not these women though. They slid on the surface of the water like eels while I struggled to catch up. Admittedly I wasn’t the best swimmer. I could hold my breath underwater for a long time; but I hated getting water in my mouth and nose.

The bathers went out far enough that my toes stopped touching the sand, where the waters were warmed by some invisible current and formed a circle. I won’t lie, I did enjoy their company. They were so sure of themselves, and they treated me like an equal. But I was fourteen and I didn’t have the experience to question that part of me that wanted to be accepted. So, as the women joined hands and tilted their heads upwards towards the sun, lost in some sort of midday trance, I found myself following my friend from afar.

Dimitris dipped in the sea with his siblings and some friends, and, just like old times, they were going for the motorboats. He must have noticed me too, he waved at me to join them. I looked back and saw the women in the same position as before, only this time they appeared less defined. Their limbs blurred into each other, their faces almost one color with the sky. And beneath the water something was moving. Bubbles rose up like the water was boiling—and indeed the water was getting warmer—but my child’s brain thought it was because the women didn’t care about politeness and had peed in the sea.

So, I left them, half-disgusted by the idea of piss all around me (although would that be anything new in the sea?) and half-excited to be joining Dimitris on another adventure again. I tried to ignore the lump in my belly that told me to steer clear of his brother.

I had forgotten how to climb into motorboats from the water, or perhaps my body had become heavier. Too slow. Something in the way the hull bobbed made me afraid I would hit my head. Dimitris was already up there so he attached the short metallic ladder to help me climb.

“Thank you,” I mumbled, too aware of how my breasts bobbed in the water while he was helping me, of my whole body in a bathing suit, and of his brother on the deck glancing my way.

On deck there were five including me. Dimitris, his sister Lukia, Ilias, a kid whose mom worked at a nearby hotel and was constantly roaming the streets, and Vasilis, the big brother. I sat crouching, trying to make my body as small as possible, become invisible until I felt confident enough to get up again. I looked to Lukia whose curves had also expanded since the last time I saw her, trying to find comfort, but she avoided my stare.

“I don’t think I can climb this again,” I said, trying to make myself feel one with the group.

That’s when I noticed Vasilis holding the anchor, a lopsided smile on his lips. “We won’t be doing that today. I’ve got the keys to this one.”

While Vasilis drove the boat toward deeper water, steadily away from the beach, I found out that he was entrusted to keep an eye on a few motorboats for some extra cash during the summer. Dimitris sipped beer from one of the cans they had sneaked from the fridge. Lukia, always down to earth, sipped Fanta, non-carbonated.

We stopped at an open stretch of water, the sun streaked down on everything. It was hard to see what was going on around the boat as the waves shone the light back at us. I couldn’t see any other swimmers or boats in the water, but in the back of my head I knew I could find the bathers, somewhere out in the open.

Then music started playing, summer songs from Lukia’s small radio. The boys balanced on the gunwale and let themselves hit the surface of the water so hard that, by the third time, me and Lukia were wet as fish. I was intent on staring at my toes coated with sand and seaweed. Neither of us made a move to dive. Lukia because she was always thinking herself the mature one, always playing mom. Me, because I’d started wondering what the hell I was doing here, mourning the boy I used to know. I had already made up my mind to not come the next day, no matter how hot it became in the city, when I heard Vasilis’s voice. His shape stood tall against the sun.

“Why don’t you come and dive with us?” I was startled to see it was Dimitris, his new voice so low, his head and shoulders peered up from the hull. Hair dripping, his arms holding to the side of the boat, muscles defined and glistening. I sensed danger in that moment, although I wasn’t sure who was in danger. Was it me or was it him?

“I don’t want to.”

“Come on. Can’t you see he is begging you?” The voice came from the stern. Vasilis leaped from the ladder onto the boat, and came toward me, body dripping. “You always do this.”

“Do what?” I started feeling cornered. Lukia seemed annoyed with all of us and stared off in the distance.

“You come and you go, and you pretend you don’t like him too.”

Vasilis loomed over me. His shadow made it easier to see Dimitris, whose face was flushed as he bit his lower lip.

“Hey, cut it out!” he said to Vasilis, but his brother pretended not to hear.

“Why? I know you like her. You keep bringing her into the kitchen. She should stop being such a jerk and come and dive with us.”

He squatted next to me and tried to grab my hand. In that moment a few things happened: Dimitris with a pained expression let his arms go and disappeared from my view. Lukia finally stopped ignoring us and screamed at Vasilis to let me be, and my body sprung up like something had taken over. I jumped into the sea and started swimming the long way toward the beach.

I heard Ilias asking what happened, and Lukia saying something, and then their voices blended with the wind and the sound of the waves, and that’s when my eyes felt wet.

I must have been swimming only for a few minutes but it felt like an eternity. Swimming and drowning in the salt of my tears instead of the brine of the sea.

“Did those boys hurt you?”

I looked up to see Miss Antigoni, her oily black hair had come loose and, in the water, had taken a life of its own, like a crown of eels. My voice stuck in my throat and I shook my head that, no, nobody had hurt me. But she could see through my lie with ease.

She caught up to me and wrapped a slender arm around my shoulders. Her skin was warm and clammy, like the mud at the bottom of the sea. It should have grossed me out but instead it made me relax.

“It’s the cycle of womanhood, my dear,” she said. “That’s how they trap you. At first, they notice you too much, and tell you everything you’re doing wrong. Everyone has an opinion. They pile more and more rules on your shoulders. Then as you grow older, the attention lessens; people lose interest in you, your value according to them diminishes. But the rules stay, and the way you react to those rules is the same. You might even become one of them and contribute to someone else’s cycle. They’ve trained you like a dog.”

“I don’t want to be a dog,” I said. I was too young to understand everything she said to me that day, but her words rang true. Through the years I came to appreciate them more. Like a fairytale that you are told again and again; and, during the repetitions you discover more nuances, lessons you had overlooked before suddenly become important.

“We’ll see about that,” she replied, but not cruelly. Miss Antigoni’s voice had a disappointed tone. “It’s hard to do otherwise. To be different is to be treated as a monster by others. But sometimes being a monster is not that bad. It’s the price you pay for freedom.”

“I am sorry about my mom,” I said, assuming she was talking about my mother’s superstitions. “Sometimes she is too much.”

“Ah, that stupid boy is coming after you.” She was looking over my shoulder, eyes gleaming with something incomprehensible. I froze, afraid of what the boy might scream at me. I was certain she meant Vasilis and that whatever he might say to me would be deeply embarrassing, like before on the boat. “Go on, swim to the beach. I’ll take care of him.”

I wasn’t sure what she meant but it took a weight off my shoulders. My mother would have scolded me, told me I should have been more prudent, and not gotten on the boat. She would have first pointed out all the ways I’d failed her, and then she would have yelled at the boy to go away. “Thank you,” I mumbled and kept swimming toward the beach that was coming closer and closer.

As I swam further from them, I wondered what she could possibly say to the boy. In my mind, Vasilis was so callous, he was unstoppable. I stopped and treaded water, and looked back.

The sun was high on the horizon and everything had a blinding white shine. But not Miss Antigoni, her body was a black hole against the sky, occupying a negative space. Vasilis had no chance, he got sucked into the whirlpool of her strength, of her being herself and something more than herself. Of being here and somewhere else. I kept looking for a few seconds and when he was completely consumed, she turned to face me. But there was no person there, only a gaping hole, its edges jagged like teeth, and through its depth came sounds. Gurgling, sucking sounds. I soon realized the sounds were coming from four different directions. They drowned out my screams. Or maybe I had dreamt I was screaming just like I had dreamt the whole thing. That’s what I told myself when I finally came out of the water and wrapped my body in the oversized towel, trying to disappear from the bathers.

• • •

When I got off the bus, I saw the bathers giving me knowing glances but they never tried to approach me again, not on the bus and not any day after that.

Later, my mother saw on the TV that a boy’s bones had washed up on the beach. We looked at each other with some sort of mute understanding.

Miss Antigoni kept her polite distance and eventually I moved on as well. I got into the nursery school in Thessaloniki and moved to the north for five years, where I met my husband. After we both earned our diplomas, we moved back to Athens, and by then Miss Antigoni and her friends were history. Women the neighbors recalled wistfully as elegant and vibrant in their old age. No matter that in the past they might have been whispering behind their backs about how inappropriate they were.

I had two children and I was needed both at home and at my job. My life was going by without a moment’s rest and I had completely forgotten about the incident at the sea until my mom fell ill and eventually died. In her last years after she had retired, she was a regular at the church, she even adopted the black scarf that many older widows wore even though my father was still alive, albeit indifferent to us. A few days before she passed, I was keeping her company by her hospital bed. She drifted in and out of consciousness, though in one moment she turned to me; her eyes were heavy-lidded and unfocused but there was triumph on her face. With a toothless smile she said, “It came to me at the store after your father left but I didn’t give in. I never gave in.”

I leaned in, knowing this might well be the last time I hear her words.

“What did?”

“The thing that comes when you’re lonely.”

“You weren’t lonely, you had me.”

She scoffed at that. “I was. You know this very well. When your father left me, people acted like I didn’t matter. Like I didn’t exist. Even you were forgetting I was your mother at times and chased after that woman.”

I hesitated. “Miss Antigoni?”

“Spit on your bosom or the Devil might hear you! Her. She had given herself to that thing. I could tell. It came for me when I was stocking the shelves. One moment my hand was there and then it was not. You hear me? I was so insignificant I would slip through the wall to—” My mother swallowed and opened her hands to show me she didn’t know where she would go but it would be somewhere horrible.

“What did you do?”

“I kept the shelves well stocked,” she whispered with pride, and her eyes drifted away from me. She never said another word.

After my mother’s death I went back to work and my family. But something inside me had changed. Everything looked strangely solid. I myself felt solid, but I couldn’t look at shelves the same way. I feared opening all kinds of doors, like the door to my closet, the door to my office. I had to make a decision that my mother’s hallucination had nothing to do with Miss Antigoni. That in her last moments, her old jealousy rose in her mind because she regretted how she’d lived her life. The only selfish decision she had made—if it could be called that—was never trying to reconnect with my father and starting a business. But the rest of her was still a woman of her time, a woman of rules, propriety, and logic. She never travelled and never splurged on anything. I am not sure she ever really had fun.

But what bugged me the most was that her character had seeped into me. I made promises to take care of myself on the days that I had time, and to not guilt my children for being themselves. Of those two I managed the second better than the first. And when the time came and they left to work and study abroad I never said a word, never held them back from becoming more. Soon my phone calls to them went unanswered or turned into text messages. There were more important things and people in their lives and that was alright. Eventually I was promoted at work but that meant more hours sitting in an office filling forms and assigning duties. My interactions diminished and it felt myself slowly disappearing from people’s minds. Even by becoming more important I was making myself less memorable at the same time. My husband was never the social type but after middle age his laziness took hold of him and by the time we were older he spent his time in front of the TV, making grunting noises at me whenever I asked something.

Whatever I tried, I was incapable of being seen again like I used to. People seemed to ignore me. No matter how interesting or upbeat I was with people, the most I could get out of them was polite condescension or complacence until they could escape my company. I felt ridiculous and needy, but worst of all I felt less solid. Invisible and immaterial. When my insomnia sent me wading through the house at night, the dark corners beckoned me. I instinctively knew that if I let myself slip in there, the borders of myself would change. I would be somewhere else, something else. I would be made anew into a creature without limits, for no one was there to trace where my limits started and ended. Nobody was watching me anymore. I would become a selfish creature ready to consume anything and anyone. Or that’s what I told myself as I tiptoed around empty spots beckoning me to fall into them. What was it really? Chaos? Rebirth? I didn’t know. So I kept restocking the shelves.

My husband died a particularly warm day in April. My children flew in for his funeral, and while they hugged and patted me on the back, they were more preoccupied with their own grief. Some of their older children were there but my daughter’s partner stayed back to take care of their toddler. My son kept brewing coffee and I kept drinking it because any attention, any show of affection was like water in the desert.

It was all short lived. Two days after the funeral they packed their things and showered me with promises. We’ll come back for summer break, Mom, and, I am looking into this lovely apartment right across the street from our place. What do you think? I nodded and promised I would think about it while we air-kissed each other and they hopped into the taxi for the airport.

Alone again, or really for the first time, I drove myself insane. The physical world was getting smaller and I was confined to tiny bits of space. I tried to be like my mother. I went to church, and bought plants to water to keep my hands occupied, and talked to the neighbors from my balcony. I volunteered for the local soup kitchen. I even dressed like a widow, let my hair go ashen and my nails grow long and jagged, hoping that the emptiness would see my resolve and leave me alone.

There came a day too hot for such dark and wooly clothes. I was trudging along the sidewalk of the main road with a river of sweat dripping down my sunken cheek. What a life, I thought. Where the hell did it go? It felt like yesterday that I was taking the bus to the beach. It was still stopping right there on the side of the road. Its doors wide open, waiting for older people with walking aids and toddlers throwing fits to board, while the driver stuffed bags of towels, swimsuits, and packaged food into the empty compartment of the undercarriage.

Just a little, I thought. Just to see what it feels like again. I didn’t even realize when my feet took me up the stairs. Any baggage? the driver asked, and I shook my head, no, this was all there was. Before I knew it, I was sitting in the front, among a couple of older women with impeccable hair and large-brimmed hats. The bus moaned before the engine started and soon we were off. I looked around but didn’t recognize anyone, and found that it didn’t bother me at all.

Soon we would arrive at the sea where there’s all the water in the world for invisible women to hide their need. All the water in the world to put out a thirst that’s been there forever.